Preface

The Chinaman Ein-lei-tung (about 2,000 BC) in his boundless wisdom, concentrated on one thing only during his entire life, namely his bamboo stick. After 50 years of deepest meditation, Tung, a man of genius, invented the bow, while stretching his bamboo stick with a bundle of horsehair. Even today we still think of him with the greatest respect. Unfortunately the original model, alleged to have had great mythical power, is irretrievably lost, but in spite of this, there are always adventurers who still go in search of the wonderful original.

Concerning the Author

The author – well, that’s me. It is possible that you, the reader, don’t really care, and just want to get down to business. But how can you understand the title without reading this introduction? Besides, I have not written many books, and therefore find it hard to pass up the opportunity to say something about myself.

My parents are psychoanalysts, both of them. But there’s no need to pity me on that account, my childhood was no worse than yours. Only different. The question “why” had great importance already at that time. And with me, that is still the case.

There are different kinds of bow makers. There are the “what” types, who are often former musicians. There are also the “how” types, who are usually craftspeople. Then there are the “how much” types, who are the dealers. I am clearly of the “why” type, the psychologists of bow making.

What I do, so to speak, is lay the bow on the couch and try to analyze it. Every little detail contains a story. The interplay of all details results in a particular character. Sometimes I also indulge in the therapy of couples. This concerns the interplay of bow and fiddle. For if the sound post in the violin is in the wrong place, one does not need to fuss around with the bow. It can happen that musicians may themselves wish to have a go at this. But this is not my style.

In accordance with my parents’ wishes, I had an academic education. But as I got older, I became more interested in both craftsmanship and music. My brother took up music. I lacked the talent for it. So I began making instruments. In fact, I found the craftsmanship part rather troublesome. My constant need to know the “why” of things was something of an irritant. As a result, I developed a kind of sound fetish. For me, a beautiful sound is an erotic experience.

So I flirted with tone production, a rather bewildering phenomenon. In this essay, I am principally concerned with how the bow contributes to the production of a tone or several tones. This is already a rather complicated process, as will soon be clear.

1.0 The Note

Chapter 1

The bow causes the string of a stringed instrument to vibrate. The vibration is transferred to the instrument via the bridge. The instrument causes the air to vibrate. We then hear this as a tone.

What we hear depends on many factors. The most important, of course, is the player. But this interests us only marginally. In fact, the player, instrument and bow act as a whole. Each of the components affects the others. But my visual attention is focussed on the part played by the bow. Not every player appreciates the importance of the bow. It is therefore interesting to try different bows from time to time. I find myself astounded again and again by the huge differences one hears. Not only is the tone different, but so are the dynamics, the whole essence of the music. It seems as if different bows also invite the musician to play differently.

The three parts of a note

My intention is to analyze these differences. What is it about the bow that gives it this individual character. My approach is not strictly scientific. As in psychology, empirical and subjective explanations are also accepted. My findings are therefore not completely provable, but I hope they will be understandable.

What complicates this exercise is that every detail of a bow affects every other detail. The character of the bow arises from the links and interrelationships of these details. To bring some order into this complicated business, a few definitions are necessary.

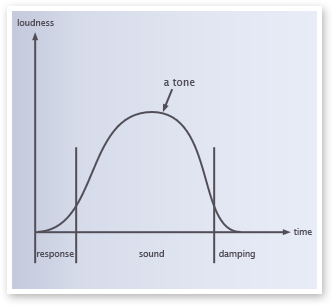

The tone is a sort of wave which swells and diminishes. This wave is divided in three parts. The swell I call the response, the diminution the damping. What takes place between them is the sound.

1.1 The Respons

Chapter 1.1

For the sake of clarity, let us first consider a single note. It begins with silence. The bow rests on the string. Since there is rosin on the bow hair, it adheres to the string. Now the player moves the bow. We can observe this as though it were happening in slow motion.

The bow accelerates, like a car starting from a full stop. But the hair still adheres to the string. The bow pulls the string in the direction of its movement. The further the string is drawn, the greater its tendency to disengage from the bow hair. The hair also pulls on the bow, which also yields, like the bow used to shoot arrows. But the string’s tendency to disengage soon overcomes the bow’s adherence to the string. At this point the string snaps back. But the bow continues moving, driving the string along like a top. There it is! The vibration begins. The way the bow causes the movement of the string to accelerate is what we call its response.

At this point a few words need to be said about the bow hair, since it is the hair, not the stick, that makes contact with the string. It matters a lot how thick the individual hairs are, how many there are, and whether these are evenly distributed. A bad job of rehairing can affect performance negatively. Reportedly, Mme. Tourte herself washed and selected bow hair with the greatest care.

Every bow has its own response, which is only achieved when the bow is properly rehaired. Just as a car needs the right tires, a bow needs more or less, thicker or finer hair. The stronger the bow, the denser the hair that is required, and the more of it that is needed.

Let us now consider how the hair rests on the string. The string’s surface forms a curve. The surface of the hairlint is flat. If the hair is tight, the point of contact between the string and the bow hair is very small. If the hair is looser, and more yielding, it can envelope the string a bit, increasing the contact surface. Therefore, a softer bow can set the string in motion more easily. In any case, more effort is needed to move the string with a firmer bow.

The response is almost or entirely inaudible, but its effect on the sound is not. The vibration that ensues depends on how aggressively the string is activated. But there is no ideal response. The best that can be hoped for is a good compromise. Above all, the bow must be compatible with the instrument, because the instrument has its own response, which affects the vibration just as much. In addition, a high note has a shorter response than a lower note, because the wave length of the higher note is shorter (Firm bows therefore work usually better for high notes, soft bows for bass notes). It also matters where the bow makes contact with the string. The string has more room to vibrate over the fingerboard than near the bridge. That affects the relationship between the grip of the bow on the string and the capacity of the string to return to its original position.

The screw makes it possible to tighten or loosen the bow, but what ultimately matters is how the bow is made, and how and where it yields. Usually, it yields the most at its weakest point, which is right behind the head. Every time a new vibration is produced, the tip of the bow bends a bit. What matters here is not so much the strength of the wood as the relationship of the weakest point to the rest of the stick. There are bows with a short, particularly weak point behind the head, and others where the stick broadens more evenly, leading to a different kind of response.

It is hard to express this in words, but what can be said is that a short, hard responsegenerally allows for more transparency, but increases the danger of incidental noise. A softer, slower response results in a rounder sound, but makes it harder to tell exactly when the tone starts. In the end, players have to pick a bow compatible with them and their instrument.

1.2 Damping

Chapter 1.2

A note is a vibration. The next note is another vibration. The bow vibrates each time the string is set in motion. If the bow stops moving, the note sounds a bit longer and dies away. A plucked string vibrates much longer. But the player uses the bow to make the instrumentplay the next tone. It is therefore desirable that the bow addresses the next note as it ought to, rather than continuing happily in the direction it was first asked to move.

The movement of the bow is a reciprocal relationship between the hair and the stick. The greater the tension on the hair, the more responsive the bow. The less the tension, the more the vibration is damped. The bow must therefore not only activate the string when moved, it must also stop it. The damping is actually inaudible, but can be felt as resistance. It is the feeling that the player can shape the note, that the bow does exactly what is asked of it, but no more.

The damping, however, affects not only the end of a note, but also the sound. The sound is in fact a specific combination of overtones. That some overtones are less strong or even entirely missing, is because they have been dampened away. One can imagine this in terms of a colour. If we see a red colour, this is red because the material absorbs the other colours of the spectrum. It is more or less the same with a note. We hear it as it is, because the other possible overtones become absorbed by the instrument and by the bow. Which overtones are absorbed depends on many things, but I will restrict myself to the function of the bow. Here the material is very important, particularly the nature of the wood, its thickness and mass, the length of fibres, the thickness relationships and the tension to which everything is subjected. There is hardly a detail of the bow which is not engaged in damping.

It is clear that the bow is a tool for producing a note, but the way it damps the tone is at least as important. That the bow too vibrates with every note can be felt by touching the stick. I will try to analyze these vibrations by concentrating on one hypothetical oscillation. This is something like concentrating on a single water molecule in the bathtub. It is very difficult. But it is absolutely certain that water molecules exist and that they move. Our vibration works the same way. It exists, and it moves. The bow rests on the string. There is no sound. When the player moves the bow, the vibration begins at the point where the bow rests on the string.

The vibration can go in two directions, forward toward the head, and backward toward the frog. I will follow the first, which moves toward the head. First, the hair vibrates. Of course, this too has a damping effect, as does every material in its respective way. But, under tension, the hair is extremely elastic. It transmits the vibration without disturbing it much. Now the vibration reaches the ivory at the tip, then the ebony, then the mass of pernambuco that constitutes the head of the bow. Even if our vibration has a powerful effect on the hair, it can hardly move the head. In addition, it has traversed a variety of materials, each with its own damping effect. It has therefore already taken something of a beating. What is left of it advances from the head to the thinnest part of the stick. There it can catch its breath, but the further it moves along, the thicker the stick becomes, which damps it again. In fact, there is not much vibration left. If we pursue the vibration the other way toward the frog, the effect is similar. The hair meets metal, ebony, metal again, and then has to leap across to the stick. But now it gets an extra weight around his neck, the silverwinding. The effect of which is rather like the damper on a tennis racket.

The two attenuated vibrations meet along the stick like two ripples in water. The ripple from the frog might be slightly stronger, since the stick is thicker at this end. Although I have no way to prove this scientifically, I assume that the combined wave moves in the direction of the head, because every wave moves in the direction where it meets least resistance. A fraction of the original vibration is transmitted back through the hair via the head. But this is so minimal as to be overwhelmed by the counter-vibration. Our vibration has been damped.

The idea that the bow’s main job in relation to the instrument has more to do with damping the tone than producing it is something that came to me only recently. But a willingness to see things this way is a key to understanding many of a bow’s details. It is possible that many makers, who have made made fantastic bows, never thought about damping. But this hardly means that the theory is wrong.

1.3 The Tone

Chapter 1.3

A bow by itself, of course, makes no sound. But when tried out on various instruments, it becomes clear that the bow produces a certain tone from each instrument. It might be that the bow produces a better tone from one instrument than another. It can therefore be said that the bow has a certain tone quality.

The tone is primarily a product of response and damping. If response is understood as thesis, and damping capacity as antithesis, the tone is the synthesis. The synthesis is new, but is subsumed in the thesis and antithesis. But is not quite correct to say that the tonal character of a bow is only determined by its response and damping capacity. Tone is identical with the vibration referred to above, and depends in turn on the player and how the instrument responds. Any reference to a bow’s tone is therefore a theoretical abstraction. The natural frequency of a violin’s top or back can be measured. How these relate to one another is highly important to the tone quality of a violin. The natural frequency of an untightened bow says very little, because a bow needs to be tightened in order to be played. Depending on the tension and pressure put on it, the natural frequency of the bow changes significantly. The most that can be said is that one bow has a higher natural frequency than another. The loudspeakers of a stereo system are an analogous case. Each speaker has a particular range of frequencies and a particular character. Every part of the system is important, even the electrical cable. The same applies to the bow. A good tone is produced when all parts or qualities of a bow combine harmoniously.

Perhaps the most important influences on the quality of the tone are the quality of wood, the parameters of its thickness, and the relationship of both to the camber of the bow. When the proportions are right, the tone is good. On the other hand, the speed of response, springiness and and strength of the bow have little to do with the sound it produces. On the contrary, it happens only rarely that these qualities combine with a nice tone in a single bow. The maker looks for a middle way that does justice to all the different demands a bow has to satisfy.

2.0 Differences according to instrument

Chapter 2.0

In principle, the demands placed on an instrument are generally the same. As Shmuel Ashkenasi says, “What I look for in a bow are basically four qualities: sound, articulating qualities (referred to above as “response”), strength and perfect balance.” But these take different forms in different instruments. The violin and viola are played in a more or less horizontal position. The cello and bass are played vertically. There are therefore clear differences in the demands on the bow. In addition, each group of instruments presents specific structural problems that the bow has to deal with,

For many years I tried to compensate for the weaknesses of the instrument by building bows in a certain way, but without much success. Vice versa works better. What is needed is a bow that goes in the same direction as the instrument. This will emphasize the instrument’s strengths and also moderate its weaknesses.

In the remarks that follow I run the risk of over-generalizing. Not all violins are alike. Every instrument has its own complicated character. But there is a certain bow for each group of instruments. In fact, I have seen violists play with cello bows. But this is an exception.

2.1 The bass bow

Chapter 2.1

I myself play the double bass a little, and my wife is a professional bass player. When I go to a concert, I therefore listen to the basses with special care. My impression is that bass entrances are chronically late – with the exception of my wife, of course. The bigger the orchestra, the later the basses come in. In fact, if you watch the basses play, it looks as if everything is right. But if you listen, what you get is something like the lag between lightning and thunder. In the latter case, what accounts for the lag is the different speed of light and sound. But so far as I know, the sound of a violin and a bass move at the same speed. Therefore, the delay we hear originates in the instrument itself. This is no surprise, considering the difference in size between a bass and a violin. The string is about three times longer. When the bow moves across the bass string at the same speed it moves across the violin string, the bass string needs a correspondingly longer time to start vibrating. The vibration must then move past the bridge (four times higher) to the top (with a surface ten times larger). Far more mass needs to be moved, and a longer path traveled, before the vibration of the string becomes audible. Therefore, a bass will always be more sluggish compared to the other instruments. This sluggishness is a challenge to the bow’s response. In the case of the bass, this means that it is especially important that the bow’s response fit the instrument. The damping capacity of the bow, on the other hand, is less important, since there is more than enough of this in the instrument itself. It has always surprised me that double basses with more than three hundred cracks and a tangle of badly-executed repairs can still sound so good. This only makes sense if the damping is understood as an important part of the tone. The repairs and cracks are actually dampers.

The instrument’s size, of course, is a damper in itself. The damping capacity of a bass bow is therefore not something that needs to be worried much about. The real problem is getting the instrument to vibrate. It is well-known that there is a French and a German way of holding the bow. The French bow is also constructed differently. Usually the French bow requires more pressure on the strings and near the bridge. This calls for a strong bow with a pronounced response. In the case of the German bow, the string tends to be drawn from the wrist, allowing the bow to be softer and lighter in order to achieve a softer response. There is also a significant difference with respect to balance. The French bow is a bit shorter, and therefore needs a much more massive head. The German bow, on the other hand, needs to be light at the tip, since it needs to cover more distance when changing from one string to another.

It makes no sense to add a German frog to a French bow. Their respective qualities should not be mixed, nor should the character of the bow be modified to compensate for the disadvantages of one or another style of holding the bow. German is German, French French, and a good musician is good, whether German, French or Greek.

In summary, response is the main issue in bass bows. Tone is largely dependent on response, because the instrument itself offers more than enough damping capacity.

2.2 The cello bow

Chapter 2.2

The cello is the instrument whose range most closely approximates the human voice. Its size, form and the way it is held lead to erotic associations that we will not go into here.

The fact is that most cellos, even very good ones, have obvious weaknesses. A wolf tone is not unusual. Most cellos have one. Those without one often sound bad over whole registers, producing weak basses or thin trebles. Others sound good over the whole range of the instrument, but produce a small sound. As previously mentioned, it is seldom possible to compensate for an instrument’s weaknesses with a particular sort of bow. Volume is often a problem. A cello has a hard time making itself heard in a duo or trio with piano. In orchestras too, a few pairs of cellos confront a whole gang of violins, although the cello is no louder than a violin.

A small digression is indicated at this point on the distinction between carrying power and volume. What I understand by volume is what the player hears. Carrying power is what the audience hears. Where volume comes from is relatively clear. The more powerfully the instrument is built, and the greater the pressure on the strings, the louder the instrument. Carrying power, on the other hand, has to do with certain sound quality, which is difficult to describe. A baroque instrument, for example, often has the same carrying power as a modern one, without being anywhere near as loud. In my opinion, the bow has little to do with carrying power, save as a bow well suited to an instrument brings out the best in it. But the bow has a lot to do with volume. The heavier the bow, and more pronounced the response, the louder the sound. Of course the bow can be too heavy and the response too pronounced, in which case the instrument squeaks and protests.

Although most 19th century cello bows weigh between 76 and 80 grams, 85 grams is not unusual today. In any case, cello bows that are both old and heavy are much in demand. At the same time, heavy bows are a disadvantage in fast passages simply because they require more weight to be moved and kept under control.

An important difference with respect to violins and violas is that cellos are played in a vertical position. The difference is especially apparent when the bow is played at the tip. As the player approaches the tip of the bow, the pressure from the bow hand diminishes significantly. This has to do with leverage. The force exerted at the frog is about four times greater than at the tip. In the case of the violin and viola, gravity, that is, the bow’s own weight, helps compensate for this loss of pressure. But gravity is not much help on the cello. This may be a reason why cello bows are about three centimeters shorter. In any case, it is especially important that the tip of the bow have a good contact with the string. The contact has to do with bow response.

As with the bass bow, but in a less extreme form, response in cello bows is also more important than damping capacity, and for the same reasons.

2.3 The viola bow

Chapter 2.3

I make a lot of viola bows. This is not because I am especially fond of them, but because they sell well. Although there are a lot of excellent old violin bows available, fine old viola bows are rare. In instrument making in general, the viola is something of a stepchild, or was, at least, till the beginning of the 20th century. But all violas suffer from a common problem, which is their size. Size and range correspond in violins and cellos. But the viola is too small for its range. Rather than 40 cm., the body of the instrument should really be 54 cm. long , a length even an American basketball player would find unplayable. As a matter of fact, the double bass is also too small for its range. Vuillaume transposed the proportions of the violin and cello to the double bass, resulting in the well-known octobass. This too is totally unusable. I know of no similar experiments with the viola. All playable violas are too small for their range, hence their characteristically squeezed sound.

For a time, big violas of 42-46 cm. length were fashionable, but many players now prefer smaller instruments, which are more comfortable to play. In any case, violas come in all forms and sizes, but only a very few produce a really convincing tone.

The bowmaker must therefore build bows for sound. It has been my experience that most violas react well to a soft response, because it reinforces the bass. It also makes the sound warmer and fuller.

In all honesty, I have hardly ever encountered a viola bow I was really enthusiastic about, although I continually run into violin and cello bows that I admire without reservation. The general rule, I would say, is that sound production should have priority over speed of response and springiness. It sometimes helps to modify the camber. There is then less tension on the hair, which produces a softer sound by increasing the damping effect. Using snakewood with it’s greater damping effect could be an alternative.

2.4 The violin bow

Chapter 2.4

The violin is the king of the stringed instruments. Just as one feels attracted to the cello, in the same way one feels overwhelmed by the violin. The violin is perfect, was already perfectwhen the 18th century began, and nothing in particular has been added to it since. The same applies to the bow. Since Tourte and Peccatte there has been no further development, at least none that I would regard as improvements. Since then there have been bowmakers who did tidier work, but without better results in tone and playability than the bows of the old masters. To be sure, good originals have become so expensive that bows made today can be worth their price. A good Tourte is about 20 times more expensive than anything the best contemporary maker dares to ask. This really is disproportionate.

In itself, the violin is loud enough relative to the other instruments that a violin bow need not be especially heavy. Light bows have the virtue of speedy and nimble response. Violinists often have rapid, virtuoso passages to play. It is therefore important to have a bow adequate to the technical demands, that bounces well and has a clear response. Unlike the larger instruments, most violins tolerate a short response without sounding dry.

But what the violin needs above all is a lot of damping. On the one hand, the violin has to damp out the shrill tones, on the other it needs to shift from a rapid spiccato to a legato without unnecessary vibration, and then come to rest again as quickly as possible.

For a bow to bounce well it needs a big camber and a lot of tension on the hair. For a sweet and quiet legato, it needs the opposite, a small camber and less tension. For rapid, rhythmic articulation it needs a short response. But this often results in a harsh tone. The many contradictory demands made on bows in general are hardest to reconcile in a violin bow. A good violin bow can only be made of the best and most elastic wood.

3.0 Weight and Balance

Chapter 3

In general, the importance of weight is overestimated because it is so easy to measure how many grams a bow weighs. But for the feel of a bow when played, balance is more important than weight per se. Balance too can be measured. I rest the bow on my index finger at the center of gravity, then measure the distance between the middle of my finger and and the frog.

| INSTRUMENT | WEIGHT | BALANCE POINT |

|---|---|---|

| Violin | 56 – 65 gr | 17 cm – 22 cm |

| Viola | 66 – 76 gr | 16 cm – 20.5 cm |

| Cello | 76 – 85 gr | 15 cm – 19 cm |

| Bass | 115 – 150 gr | 10 cm – 13.5 cm |

Of course, there are bows that exceed these values, but in my opinion the ideal measures lie somewhere toward the midpoint of the figures in the table.

As a rule, heavy bows are loud, but awkward to handle. This tendency is reinforced when the center of gravity is toward the tip, that is, when the bow is topheavy. This is because weight at the tip is more noticeable than more weight at the frog.

Light bows are usually preferable to heavy bows, provided that they are not too soft. These can, even should, have their center of gravity somewhere toward the tip. The advantage of a somewhat topheavy bow is that it tracks well, that is, that they continue easily in the direction in which they are moved. Their disadvantage is that they make quick string crossings more difficult. Whether more weight at the tip assures more contact is unclear. The contact with the string at the tip of the bow has more to do with the relationship between the camber, the strength of the wood, and possibly the flexibility of the stick, than with the weight of the bow and its distribution.

Weight and balance have little direct effect on the quality of tone, it’s more a matter of playing technique. To be sure, volume and ease of playing have an indirect influence on the sound. It is easier to concentrate on sound production when the player is technically confident, without feeling a need to play as loudly as possible.

What is certain is that the combination of weight and balance is impartant in a bow. Weight by itself says little.

4.0 The wood

Chapter 4

Most bows are made of pernambuco, a wood that comes from Brazil. In fact, instead of gold, Vespucci (1451-1512) brought home a red wood from Brazil, that the Portuguese called pao brazil. At the time, the wood was used in the production of red dye. In Amsterdam we still have the “rasphuis” where female prisoners had to rasp pernambuco. There is an old description of those poor woman with tears running through the dust on their faces.

Originally the wood came from a region still known as Pernambuco, although there is no longer a single pernambuco tree there. Today pernambuco comes from other, more humid parts of Brazil. There the wood grows faster, and rarely has the quality that was still common in the 19th century. But when chosen carefully, good pernambuco can still be found.

Other kinds of wood are also used. Snakewood, mentioned earlier in connection with viola bows, is primarily used for baroque bows. In the transitional peiod between the baroque and the modern, there were experiments with ironwood. Actually, this is a generic category for a variety of tropical hardwoods, still known today by a confusing variety of names. I have personally had few good experiences with ironwood, but it is entirely possible that several species have the advantages associated with pernambuco. Cheap bows are often made of brazilwood, which is related to pernambuco, but clearly makes for inferior bows.

To be sure, pernambuco too differs signicantly in quality. It is practically impossible to judge a whole trunk. In any case, I have so often been disappointed that I have learned to be careful. When I go through a bundle of wood, I buy 10% at most, usually less. What I first look at is weight. If the boards are all cut alike, weight differences are perceptible. The heaviest are the densest wood. If the grain is relatively straight, it is worth cutting the board into sticks. The direction of the grain shows how straight the wood has grown. There are often different colored stripes in the wood, which can be misleading, because they may not go in the same direction as the grain, but are much more conspicuous, although they have no effect on the quality of the wood.

The first two criteria are therefore density and linearity. If one wants to know the density, it suffices to cut off a small piece and throw it in a glass of water. If it sinks, its specific gravity is greater than water, which is cause to rejoice. If it floats, the wood is relatively porous. It can still make a good bow if enough attention is paid to this in the construction. But a heavy bow can not be made of light wood. This sounds simple, but it took me some years of practice to learn.

The advantage that porous wood often has is its greater elasticity. This is a difficult concept in principle, but it works like this: hold on to a stick firmly at one end, lay the other on a firm surface, e.g., a table, and push on the middle of the stick with the free hand. What matters is not so much the effort needed to bend the stick – this has more to do with its thickness – as the way the stick returns to its original state. This is elasticity. The elasticity of a given bow depends on the length of the individual wood fibers, which is hard to judge with the naked eye. A device developed by G. Lucchi, my former teacher in Cremona, is useful here. It transmits ultrasound at a certain frequency through the wood. The faster the ultrasound passes through the wood, the more elastic it is. This can be misleading, because numbers are always seductive. But given adequate caution in the interpretation of the data, the device is a good thing, even though generations of bow makers managed without it.

If the wood is very elastic, care is required to keep the bow from becoming too nervous. If the wood is less elastic, it should make a stronger bow, with a full camber. The idea is to compensate for elasticity with more tension. Greater elasticity is surely an advantage. But it is more important that the concept of the bow correspond to the quality of the wood.

The way the stick is cut is extremely important. First, the saw has to follow the grain of the wood as closely as possible, while avoiding all possible branches and cracks. Second, one needs to be aware of how the annular rings are positioned in the stick.

Two considerations are involved here. The first is the risk of breakage. All wood splits or cracks at a right angle to the annual rings. This can be clearly seen in a bundle of firewood. The cracks all point in a star pattern toward the middle. When wood is split, this is also done at a right angle to the annular rings. The head of every bow is higher than it is wide. If the annular rings are horizontal with respect to the head, the bow should split in a vertical direction. But that rarely happens, since even a violin bow is two centimeters thick in this direction.

But when the annual rings are vertical with respect to the head, the bow breaks across. The width of the head is only five millimeters thick, therefore the bow breaks more easily in that direction. I can demonstrate this with a practical example. A few years ago I copied a very fine Pfretzschner violin bow. The copy was a great success, save that I overlooked the annular rings. In the original they lay across the head. In my bow they were vertical with respect to the head. After about 10 minutes of playing, the head broke off. The player, a well known violinist, was horrified. Since then I know that, when the annual rings stand upright, the head has to be as massive as possible.

Were the danger of breakage the only question, things would be easy. Unfortunately there is another problem. The wood is strongest in the direction of the annular rings. Seen in this perspective, it would be an advantage if they were vertical with respect to the head. Or still better, they would correspond to the angle at which the bow is played, which is not exactly vertical. Violinists and violists tip the bow slightly to the right, cellists and bass players to the left. The ideal position of the annual rings is therefore at an angle to the plane of the bow, with a somewhat horizontal tilt. In this way the danger of breakage can be minimized while, at the same time, the full strength of the wood is brought to bear in the movement of the bow.

Unfortunately, a straight, highly elastic stick of very dense wood with the annular rings in exactly the right place is a rare exception. Almost every stick confronts the bowmaker with imperfect material. The art is to match the model and design to the wood in such a way as to minimize the shortcomings of the material. A small trick, for example: when the annular rings lie at an angle to the string, but in the wrong direction, the stick can be cut so that its cross-section is oval rather than round in the playing direction. This weakens it in the direction of the annular rings, but strengthens it in the direction the bow is played by the musician.

The ultimate quality of a bow depends about 50% on the quality of the stick, but the other half is the use that is made of a particular piece of wood.

If one buys fresh wood, this is best left to mature, sawn into planks, for about seven years. The wood is already dry after about half a year. But the tensions that exist in every piece of wood, take very long to sort themselves out. And when one has sawn the wood into sticks, it has to be lain aiside once again, so that the tensions can find a new balance.

If one wishes to ensure that the finished bow will not move any further, one must allow as much time as possible between different handlings. The wilder the wood, the longer a stick needs to calm itself down. Looked at in this way, one can say that a bow needs at least ten years before it becomes finally ready for use.

5.0 Colour and Varnish

Chapter 5

Color and varnish in bows are less complicated than in instruments. Nonetheless it took me many years to attain a clean finish. A bad finish can spoil an attractive piece of wood. A good finish can enhance its appearance. The most attractive finish however is aged, dark wood with a full but thin shellac polish. Old wood radiates a warmth unknown in new wood. This has less to do with varnish than the surface of the wood, which changes with age. Of course, it becomes darker, but above all the transparency changes. The wood grows increasingly matt. With less light, the wood is darker. But if held under a lamp, it seems to glow from inside. The wilder the growth, the more attractive it is to look at. The flames appear so to speak because the wood fibers run in and out of the stick. According to the angles the light is mirrored differently.

I have tried everything from rabbit dung to an overdose of gamma radiation to imitate this aging proces, but with little success. The only useful agent is nitric acid. I believe this was already used in the 19th century. The advantage of nitric acid with respect to other coloring agents is that it reacts with the dye in the wood, and etches its surface a bit. In the process, the surface becomes a bit uneven, which softens the reflection. Unfortunately, the softer reflection brought about by artificial aging has a different character than natural aging, so the nitric acid treatment remains visible as an imitation. Other coloring agents penetrate the wood less deeply.

If the varnish becomes somewhat damaged, then the treatment with acid does not bring the bright orange wood directly to the fore. But nitric acid conceals its own dangers. If it is not sufficiently neutralised, then deep black spots form underneath the varnish, which look very ugly. If a bow has been handled with acid, one can see the pores are very black. This also is optically very disadvantageous.

Unfortunately, customers usually prefer dark bows to light. For the most part this is unconscious. Good, old bows are expected to be dark. There is therefore a tendency to confuse dark with good. Actually, the color of the stick has little to do with its quality. Dark wood has more coloring material in it, light has less. It is possible that light wood tends to be somewhat more porous, but also more elastic, while dark wood is denser and less resilient. But this is not always the case.

Ordinarily, pure shellac is used as varnish. All other resins leave a heavier coat on the stick, which only impedes its movement. Shellac, on the other hand, can be applied in very thin layers and, with a bit of patience and a fine abrasive, the pores can be closed. “If you want to fill the pores, use a pore filler”, Roger Hargrave once told me. Since then, I tell myself the same thing everytime I have some polishing to do. Closed pores give the impression of greater compactness. But this is a purely aesthetic consideration. What matters to the sound is that there be as little varnish as possible on the bow.

On the other hand, shellac is sometimes too glassy, and gives off a hard reflection. I therefore apply a thin layer of linseed oil to the raw bow, let it soak in, then polish it. In this way, the varnish is somewhat more matt, the reflection somewhat softer. The varnish itself should not be conspicuous. What should be seen is the wood.

Synthetic varnish gives off a somewhat harder reflection of light and is often somewhat cold and whitish. On the other hand, it can be quickly applied. I nonetheless advise against it. I need at least two weeks to varnish a bow, often longer. Every layer should be allowed as much time as possible to dry. Then it should be moistened again by polishing with alcohol, and if the previous layer is not totally set, it comes off, which is exasperating.

Although polishing is not a creative activity, it is worth the trouble.

6.0 Distribution of Strength

Chapter 6

The bow that shoots arrows and the bow that plays stringed instruments have something in common. The former is also tightened so that it can be used for hunting. When the wild boar breaks out from the thicket, the string is pulled and and an arrow is shot. But when the hunter tightens his bow too much and it breaks, he has a serious problem. All he can do is climb up a tree. When the violin bow is pulled too tight and breaks during a councert it’s also pretty bad, and no trees around.

The moment of shooting an arrow corresponds more or less to playing a stringed instrument in a concert, even if the audience facing the player is less dangerous. The comparison could be taken still further, but I will limit myself for the moment to the problem of the breaking point. The tension and force that a bow sustains cannot be greater than the tolerance at the weakest point (for familiar reasons).

Normally, the head is the weakest point. The grain of the wood runs along, or more accurately, through the stick and on to the head. But it is unattached to the lower part of the head.

Therefore, the midpoint of the head is usually the weakest point. The extent of the danger has to do in part with the position of the annual rings (see the chapter on wood), but also the form of the head. A robust stick requires a larger head. A soft stick will tolerate a finer head, because less force is brought to bear on the vulnerable point. If the risk of a break were all that is involved, the head would be as low as possible. In baroque bows, this is actually the case. But over the course of time, bows have been built to produce a bigger sound with as much tension and camber as possible. The vibration of the hair increases the tension on the head. The more pressure the player exerts, the greater the tension.

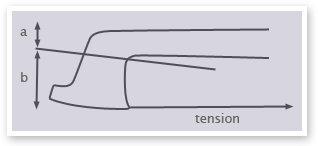

The higher the lower part “b” in relation to the upper part “a,” the greater the leverage. The greater the leverage, the more powerfully the vibrations are transferred to the stick. The height of the head therefore has a major effect on the movement of the stick. Moving a more robust stick requires a more powerful “input.” There is otherwise too little amplifier for a too large loudspeaker.

Two conflicting criteria must therefore be considered for the function of the head. One is the risk of breakage, that can be met by lowering the head. On the other hand, a higher head transmits vibrations much better. This makes the bow more sensitive, even when it is powerfully built.

The strength of a bow is impossible to express in numbers. Usually a player says that a bow is powerful if the stick remains above the string even when playing forte. But a more flexible bow can also give the sense of power if other relationships are right. The first important point is that the strength of the bow must be equally distributed across its length. Lateral stability is equally important. A powerful bow that bends laterally is more likely to overplay than a softer bow with lateral stability. To analyze a bow, these characteristics have to be considered.

When a bow is loosened, the strength of the stick in vertical direction can be measured by resting the bow on its ends, and hanging a 250-gram weight from the middle. A violin bow will gave way by about one and a half to two centimeters, a cello bow by half of that. Many bowmakers use such a device. Anything measurable seems to us nicely objective, but the objectivity should not be overestimated. No one plays with a loosened bow.

As soon as the bow is tightened, its strength become a function of the stick’s elasticity, the thickness of the wood and the camber. The match between wood strength and camber can be tested by tightening the bow until the stick is straight. But please don’t do it yourself! Even if the bow is well-insured, the test is best left to the bowmaker. If the stick is really straight, camber and wood strength are properly matched.

There are various possibilities for distributing the camber and the thickness of the wood along the stick. The bows of the last century (19th) mostly have the most curve in the middle of the bow, but in the course of time, this point has shifted towards the tip. My own impression is that bows with little wood and a lot of camber at the tip respond well, but sound somewhat thin. More camber in the middle produces a fuller sound, although the response is not as accurate. But these are general tendencies, because a bow’s sound and response depend on many factors. Any concept can work well if the relationship of the camber to the quality and conformation of the wood is right. When this is not the case, the player has the feeling of losing contact with the string at a certain point.

Even when the camber and the quality of the wood are properly coordinated, what matters is how much bend there is in the bow. When the loosened bow touches the hair, this is called a full camber. The opposite state consists, for example, in a five-millimeter separation between the hair and the stick. The appropriate camber can vary from bow to bow. Too much will make the bow nervous, make it scratch, and cause it to thrust out to the side. Too little makes the bow lame, and causes an irregular bounce, although it can also make the tone nice and round. A full camber is especially good for the bounce, while less camber relaxes the sound and increases the bow’s lateral stability.

If the bow has too much strength in the vertical direction, it gives way laterally, with a loss of energy. The same bow with less camber will be more stable, and therefore more powerful. How much camber is right for any given bow depends on the material, the player’s taste, and the instrument. Bows where all conditions match one hundred percent are rare, but most players are so accustomed to their bows’ “moods” that they compensate automatically by adjusting their technique to the bow. But occasionally the bowmaker can achieve a mini-miracle with a slight change in the camber. Sometimes remarkably little is needed to restore a bow’s equilibrium, and it then sounds and works much better.

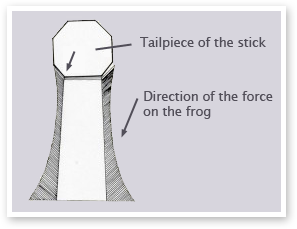

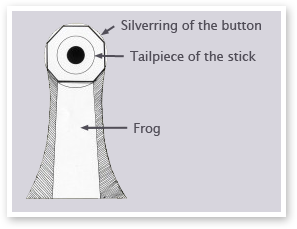

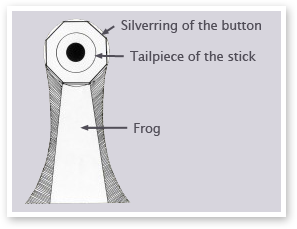

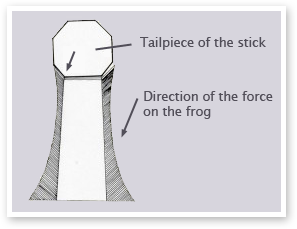

In the transfer of strength from the hair to the stick, the tip naturally is not the only important thing, the frog is just as important. In principle, the same considerations apply as to the tip, only the region of the frog is somewhat more complicated.

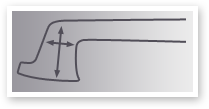

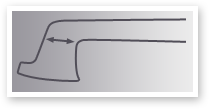

If the bow is tensed, then the frog sits securely on the stick. The only movement it still has to make is a slight turning towards the stick (or revolving in the direction of the hair, or around the brass nut). Even the smallest pressure given the bow by the musician while playing works itself out in this small turning movement.

A particularly tall frog creates greater leverage, and in this way, the situation is exactly the same as for the tip. But with the frog, the strength works itself out from the turning movement at the near end of its base. So the distance from the brass nut, which holds the frog firmly in place, to the near end of the base, also has a part to play. This length is also a lever, only the opposite way.

A long base lessens the strength of the leverage. A tall frog with a short base, therefore, makes for the strongest transference of the vibrations of the hair on to the stick.

How strong this transference should be, depends upon the opposing strength of the stickat this point. The opposing strength given by the stick depends again on the thickness of the wood and the curve in the region of the frog. A bow that is thinner at the end than in the middle is best matched to a low frog with a long foot. A bow whose thickest point, with much curve at the frog, needs a fairly high frog with a short foot. But very high frogs have another disadvantage, which is that they lose lateral stability.

Many of the old French bowmakers made the middle track on the underslide beneath the frog broader than the lateral tracks. The reason must be that the player’s middle and ring fingers rest on the frog, and thereby exercise some lateral pressure. In addition, the bow seldom lies flat on the string, but is tipped a bit. This increases the lateral pressure on violins and violas, which tilt to the right. But in the case of cellos and basses, which tilt to the left, the pressure of the fingers on the bow and the pressure arising from the tilted bow cancel one another out.

The broader the middle track of the underslide, the more resistent is the frog to lateral pressure. But there is a bit of leverage here too. The breadth of the middle track of the underslide should therefore increase with the height of the frog.

Every detail and measurement of the bow is functionally related to every other detail. The smallest change affects the whole bow. Therefore, no two bows are exactly identical, irrespective of differences in the quality of the wood, and this is the basis of every concept.

7.0 Aesthetics

Chapter 7

There is no absolute objectivity in aesthetics. There are only individual ways of looking at things.

Our brains compare everything we see, whether natural or manmade, with familiar objects that are similar. The observer evaluates and classifies the ‘object’ according to his or her experience. It is therefore impossible to look at anything without prior assumptions. Our experience leads unconsciously to expectations. If the object meets or exceeds them, we feel secure or are pleasantly surprised. If it fails to meet them, we don’t like it or try to ignore it.

While learning the trade I tried as hard as I could to revolutionize bowmaking. I did everything as differently as possible, naturally without much resonance or success. What we like depends on what we know, and if novelty deviates too far from this, most people will reject it.

There are nonetheless a lot of people who agree on what they like. All we can conclude from this is that they share a common experience. This is culturally conditioned, of course. We need to presume this cultural consensus in order to talk and understand one another. Someone from a different culture often understands a given statement quite differently from the way we ordinarily do. He or she finds different things funny or beautiful. Our aesthetic taste is also a matter of cultural conditioning, deriving from our experience and education.

Finding things beautiful is also a culturally determined affair, since it depends upon our experience and our upbringing. Well, one must now ask oneself just how important it is, how a bow looks. In point of fact, every detail of a bow, every design of its contour has a functional reason. The only exception is the nose, the frontal tip of the bow. In the Baroque period, every shape had to end in a flourish. The nose of the bow is a relic from that time of the Baroque bow; it has no functional reason. But one has grown so accustomed to it, that a bow without one would be found extremely ugly.

A bow is not an objet d’art. Its development has been primarily determined by function, with the goal of making it louder, stronger, more aggressive. Aesthetic appearance was secondary, equivalent to the spinach served as a side dish to the main course. If the spinach is oversalted, it may be an annoyance. But no one would judge the main course by the spinach.

On the other hand, aesthetics should not be underestimated either. The magic that radiates from a master craftsman’s beautiful old bow is a source of pleasure for the connoisseur. A large part of this has to do with the quality of old wood. An old bow maker once told me, many years ago, that with good pernambuco wood it is like having the feeling one could look into the wood as one would into a lake. This is a romantic description, but I can not think of a better one.

Whereas there is relatively close agreement as to what constitutes good wood, the shaping of the lines of a bow is, to a large extent, a matter of taste. Unfortunately, our taste is very dependent on what we are accustomed to, and also on the sheer price of a bow. It is much harder for anyone to find a very expensive bow awful than to disapprove of a cheap one. Nobody likes to admit this to himself. However, it is the case that something which is worth a lot of money inspires us with much respect. When one buys something that clearly oversteps the limits of ones budget, then one loves that thing more, since one has bought something one could not really afford. Musicians normally are not madly keen on having an expensive car, but a too expensive instrument or a too expensive bow gives them much joy. It spurs them on to higher achievements, instead of their just hating the idea, which would be a reasonable reaction. That is a paradox from which we all suffer.

Astonishingly enough, connoisseurs are more or less agreed on the subject of what constitutes a good bow, apart from the wood and the price. It is naturally true that the longer one has had to do with bows, the more details one can see in them. And the more details one recognises, the nearer one gets to the essence of a bow. At the same time, however, the connoisseur is more careful in his judgement. There are bows which one finds beautiful at first sight, but which lose their fascination the more one contemplates them. Others that one had not particularly liked at first gain sympathy with time. What appeals to people straight away probably has to do with the degree of familiarity of the observed shapes. The slowly arising sympathy comes, however, from the more genuine understanding of the object in question. This is the build-up of a relationship between object and observer.

The relationship naturally remains subjective. But there are objects, in this case bows, which favor such relationships, and others which have less appeal to the experienced observer. In my opinion, the intensity of the relationship depends on how much love, timeand competence have been invested in a given bow. For the observer, careful craftsmanship or a particular profile are not the issue. On the contrary, less carefully crafted bows may have more appeal for us. Their imperfections can inspire sympathy, and may encourage the instinctive understanding needed for a feeling of affinity for a bow. A good bow is a complicated statement, that can subsume an inner harmony not always recognizable at first sight. But when it is there, there is a growing affinity for the bow, and respect and sympathy increase perceptibly. This happens more often with bows made by well-known makers, not only because they are expensive, but because the makers, each in his or her way, have taken particular care with the materials.

Beauty is not an accident, but a result of intense desire plus deep thought and professional skill.

8.0 A Dominique Peccatte Bow

Chapter 8

In my opinion, this is a true Dom. Peccatte. The tip may have been shortened a little by someone who replaced the ivory. This happened to many, even most old bows. The frog is also worn, or probably filed down to do accommodate a musician’s thumb. Every old bow is worn to a certain extent. The viewer usually compensates automatically for that when looking at it. The bow gives a very compact impression. That means that every part of the bow belongs to the whole, every part is made by the same hand, and every part is worn to a similar extent. Most of the characteristics one would expect from a Peccatte bow are there, but not all. That is not unusual. None of Peccatte’s bows has every characteristic associated with him. On the contrary, if a bow shows every characteristic too obviously, it is probably a copy. Unfortunately, this bow has several hairline cracks, which can not be seen in the picture, but are definitely there. One is about ten centimeters long and so thick that I assume it has been open, and reglued. In fact, considering how many cracks it has, it is a wonder that this bow still plays. The wonder merits a bit of investigation. First, the fibres of the wood are exeptionally straight. Therefore run the cracks absolutely straight along the stick. If a crack is diagonal to the stick, the bow will break immediately, and is usually beyond repair. But in this case, the stick has survived seven or eight cracks, and still playes well. It feels a bit tired in the hand. But there are musicians who like that. There is also a crack in the head, in fact, two of them. This is normally fatal. But it has little effect on this bow. Actually these cracks stand vertically in the direction of the head. Wood breaks most easily at a right angle to the annular rings. So we can deduce from this the direction of the annular rings. They lie horizontally in the head. This is also visible with the bow in the hand. By knowing the directon of the annular rings, one can predict the direction a brake would take. A diagonal break in the head means a total loss. But in this case, where the cracks stand precisely vertical, a bow can survive, because in this case, when the bow is thightened, there is no stress on the cracks. The bow therefore makes an effective case that horizontal annular rings in the head protect a bow against breakage.

I assume that all of these cracks are very old. From the history of the bow, I know that they have been there for at least 40 years. But I presume that they were also in the wood when the bow was made, because cracks of this sort usually occur in pernambuco while it is stored as planks or rough sticks. Perhaps they were scarcely visible, or Peccatte knew they were harmless because of the direction of the annular rings in this stick.

In the argument that follows, the annular rings are also a key to understanding the bow. The second astonishing fact I found in this bow is the cross-section of the stick.

| Bowhead | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | cm distance from head |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 6 | 8 | 7.5 | 7.8 | 8.2 | 8.4 | 8.4 | mm vertical heigt |

| 4.8 | 5.9 | 6.8 | 7.3 | 7.6 | 7.8 | 8.2 | 8.4 | mm horizontal width |

The cross-section is not round at all. The stick is over the whole length higher than it is wide. The cross-section forms an oval in the vertical direction. The difference between height and width is too obvious and regular to think it could be a coincidence. So I presume there was a reason why maitre Peccatte did it that way. The reason, in my opinion, is …( what else ? ) The position of the annular rings. Every wood is the strongest in the direction of its annular rings, so it is in the nature of this stick to be stronger towards the sides than in the playing direction. It could be that maitre Peccatte didn’t like this. It could also be that, while he worked on the stick at a certain point, it was still too heavy, and he had to decide where to take off some wood without weakening the bow too much in the playing direction. So he planed the sides, and the stick became oval. This was apparently not a problem for him. He may even have wanted it this way. In fact, this made the bow evenly strong in all directions. Towars the sides, the strength is based on the annular rings. In the vertical direction it comes from the oval form of the stick.

I believe that Peccatte was very concious of these things, but most people see him as a more intuitive worker. Who knows ? But the outlines of this bowhead also show that he knew exactly what he was doing, conciously or unconciously. Actually one of the main characteristics of his other bowheads is a form which is quite safe against breakage. The classical point of breakage is in the head of the bow precisely in the prolongation of the underside of the stick.

Peccatte cuts the backside of his heads in a relatively big arch in order to strenghten the bowhead against breakage at its weakest point. That must be his reason, because there is no aesthetic advantage in it. This is his usual practice, but not in the case of the bow shown in the picture. Here the line of the backside of the head reaches far into the corner, much further than might be expected in a Dom. Peccatte bow. My explanation is again the same. The horizontal annular rings guarantee a lot of safety against breakage, so this bowhead does not need an especially secure form. Obviously this is the case, because this head has two cracks, and still does not break. Consciously or unconsciously, Peccatte could afford to make a more elegant outline because of the direction of the annular rings. What makes a Dom. Peccatte bow so attractive is its inner logic and harmony. It is the beauty arising from the function that makes his bows so convincing.

9.0 A Maire Bow

Chapter 9

Some years ago I was able to acquire a Nicolas Maire bow so badly damaged as to be irreparable. I have to date made several copies of this bow. None of them are perfect, but each time I have made new discoveries in the process of copying it.

Most unusually, the middle part of this stick is clearly oval, but it is wider than high. For many years I thought, that the cross-section of a good bow was round, but this one is a flat oval, just the opposite of the Peccatte bow, where the oval is more like an egg, and both of them are very nice items. Now lets have a look at the cross-section of this Maire bow.

| Bowhead | 15 | 30 | 45 | 60 | cm distance from head |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.8 | 6 | 7.5 | 7.8 | 8.4 | mm vertical heigt |

| 5.4 | 6.8 | 8 | 8.2 | 8.3 | mm horizontal width |

Looking at the vertical measurements the bow is very thick behind the head. That would be a healthy measurement for a viola bow. In comparisen to this is the bow extremely thin in the middle of the stick. The horizontal measurements are pretty much what one expects from a good stick. But why made N. Maire this bow so flat oval is the first question.

Obviously the oval form in the middle of the stick lends greater stability to the sides. At the same time the bow retains its vertical flexibility. Near the frog and behind the head, where the oscillation of the stick is very small anyway, the bow does not need lateral stability, hence there is no advantage in making it oval there. So much to the width of this stick.

Let’s look at the height. As I already said, this bow is very strong behind the head and very thin in the middle of the stick. This bow is soft in the middle and hard and heavy at the tip. That is nearly a barok concept of a bow. At least in this century all bowmakers try to do the opposite, stiff in the middle and thin at the tip. That makes a bow easier to handle,but for the sound Maire’s concept might have some advantages what all those new bows miss. A conical stick damps down the vibration more effectively than a stick where the thickness is overall about the same. Thats why this concept helps to develop a good sound, but technically this bow must be somewhat more difficult. A heavy tip is slowlier in changing strings and if the stick behind the head is stiff the bow doesn’t grip the string so well at the tip. Usually a modern bow reacts the most sensitive in the area just behind the head. This bow has its most sensitive spot in the middle of the bow. And that is the spot where the musician plays the most of time. That seems to me an advantage of Maire’s concept. Also the rather heavy tip has an importend advantage, the bow lies safely in the string and keeps its direction very well. All this together could make a sweet but a bit lifeless bow. To avoid this there must have been quite a full curve, which the bow probably had. But on my bow the original curve one can only guess. So I assume the bow had quite a full curve, because that way it brings back some lifelyness in the stick, the tension of a full curve helps to create a good spiccato, and the oval form prevents the stick from breaking out to the sides (Which is the danger of a full curve). All together the bow makes a lot of sense.

Are there any disadvantages of this concept ?

After copying the Maire bow a couple of times certain characteristics of tis model became evident. While the sound is full and round and therefore mixes well with other instruments,it lacks penetration. Rather than singing out above an orchestra, it tends to be drowned in it. The player can create a sound that is sweet and noble, but it could benefit from being somewhat more fresh and transparent. The sound carries well, but it is not very loud under the musicians ear, which could be rather a hindrence for orchestral musicians, who need to hear themselfs with a trombone blowing in their ear.

The weight of this bow is at a good medium of 60 gms. It is a little topheavy though, which is not to every player’s taste.

From the point of view of aesthtetics, the frog seems to be worked with greater care than the tip. The two sides of the tip differ greatly, the lower surface (where the ivory tip sits on) is lopsided, and the transition from the head to the stick is rather negligently executed.

At this point the interested reader might think : “so maybe this is not a real Maire, after all”. But you consider that in those days a bowmaker would have had to make around ten bows a month, it is easy to imagine, that sometimes they were quite pressed for time. Maybe this stick was the last in the series of ten and our master was already bored. Maybe he had also a headache from the sour wine that was consumed in those days.

The bow is mounted in nickel, which then, as today, would have been inexpensive. Quite possibly a dealer from Paris would have bargained the price, so master Maire had to economise on his time and effort.

The butten is quite short in fact, normally they are longer as far as I know. But it is anyway in a poor state. I believe it has been tampered with by some well-meaning, but poor skilled repairer. Therefore I shall not deal with it further.

The frog itself is in mint condition and very carefully made, even though it is mounted in nickel. There is one detail about the way the frog is fitted to the stick, the meaning of which I only understood recentely. With my own models, so far, I have always made the stick a regular octagon, with all sides exactely the same width. This way it was possible to achieve a perfect fit with the button, which is also even-sided.

But on the Maire bow and so many other bows of that period, the eight sides are not the same size. The lowest side – the one that makes the most contact with the stick – is significantly wider than the others.

The reason for this is the lateral stability of the frog. This is important because when a bow is drawn across a string the pressure of the middle finger on the frog, as well as the sideways tilt of the bow while it is being played, conspire to slightly tilt the frog around the stick. – Got it ? If not then read it again. – This results in a lot of pressure being concentrated on one corner of the octagon.

The further out towards the side this corner is moved, the more stable the frog sits on the stick. So that is the advantage of this construction, as disadvantage you could see the fact, that the other two sides which make contact with the stick get smaller and thinner, and therefore more fragil. The corresponding sides of the stick get also thinner, and on one of them the musicians thumb is placed. The broader this side is , the more contact the thumb makes and that gives a safer feeling to the player. On the whole though, it seems that the advantage far outweighs the potential inconvenience.

It is important to understand that a bow is a concept, in which every detail has to contribute to producing a functioning whole. Everything about it has an impact on the result, including how the inside of the frog is made, the shape of the mortice, its place, width and depth, there is always a reason for everything.

10.0 A Cello Bow by Dodd

Chapter 10

This bow is a masterpiece. It gives an impression of strenght and elegance at the same time. It also units perfection and warmth in one whole. To bring all those things together, makes a very special bow.

What is the most impressif at the fist view is the quality of the wood. The ebony is jetblack without any pores at all. Only some little shiny lines can be seen. The pernambuco is quite dark, a dark brown you could call it, with black stripes going along the stick. Also this without any visible pores. When you put it under the light it glows up in a red ruby, that is pretty overwhelming. Such dense and compact pernambuco is not to find nowadays. In fact, some people think it is not pernambuco what Dodd and Tubbs used for some of their bows. They think it is a related species of pernambuco with the somewhat helpless name “english pernambuco”. I personally don’t believe this, but I can imagine that this wood is grown on a very dry place, where the wood grows slowly. It could take 200 jears to make a cross-section of 20 centimeters. That was probably in pernambuco, a part of Brasil, where you can’t find a single pernambuco tree anymore. In that case this stick would be the real pernamuco and what we use now is a somehow related species.

In any case is this stick incredibly dense. Often is dense wood less elastic, heavy but a little weak. That is absolutely not the case with this bow. It’s elasticity is relatively high, measured with Lucchi’s elasticity-meter it shows a 5500. Which is quite high for an old bow. So the first statement is: very strong and dense wood. The whole concept of this bow based on that fact.

This is an octagonal stick as you can see in the picture. What’s curious about it, is that the sides are very uneven. A cross-section through the middle of the bow would look like that.

| Side | Mm |

|---|---|

| Vertical height | 9.2 |

| Horizontal width | 9.2 |

| Diagonal left | 8.8 |

| Diagonal right | 8.8 |

That is astonishing, because usually it is the other way around. The four sides in the vertical and horizontal direction are usually broader than the diagonal ones.

Now let’s find some reasons, why Dodd did it that way. I can imagine it has to do with the fact, that one doesn’t pose a bow completely vertical on the string. The bow is a little tilted to one side. So the pressure the musician gives while playing forte is more in the diagonal, than in the vertical direction of our octagonal stick.

That means, that Dodd weakend the stick in the playing direction. Today every body wants to make a bow as strong as possible. To weaken a bow seems to be an odd idea. But looking at the nature of this pernamuco, it begins to make sens.The wood is too strong, what gives a too short response, and Dodd just went there and weakend the bow until he liked the sound.

Another point of view is the aesthetic side of a bow. This way the optical effect is that the bow seems to be thinner and more slender, than what it is. That gives an impression of dampend power, strenght without showing off. This bow is absolutely noble.

The precise measurements are:

| Bowhead | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | mm distance from head |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7.2 | 7.7 | 8.4 | 9.2 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 9.6 | mm cross-section |

The measurements in vertical and horizontal directions are absolutely the same. Dodd must have measured very carefully, it is exact on a tenth of a millimeter.

Dodd left the stick behind the head pretty thick. Also the head itself is on the healthy side. Well, the bowhead is quite high, 28.5 m, and the higher the head, the bigger the lever on the stick. Dodd didn’t take any risk for breakage, but the bow became very heavy, 87 gms.

The frog is built very light, because there is hardly any silver on, just a thin ring to spread the hair. So the whole weight is in the stick, and a lot of it at the tip. That makes the balancepoint move to the tip and the bow becomes what I call “tipheavy”.

This bow has a stupendous sound with a warm heart. The spiccato is also goed, this is because of the high head and a pretty full curve. But the bow stays heavy in the hand, fast change of strings are hard to do. This is the only little disadvantage I can find. Further is it a great bow, also aesthetically a pure delight.

11.0 How to evaluate a bow

Chapter 11

It’s a common mistake to think you hear with your ears. You hear with your brain.

Your ear is some sort of a microphone that transmits a soundwave into an electromagnetic impulse, which is analysed in your brain. All your senses continously send information to your brain. Combining all the incoming information to each other and comparing that to stored similar situations our brain builds up a virtual reality and decides what action has to be taken. Our brain is designed to survive in this world. The main question is: Is it life-endangering ? Therefore everything that moves gets more attention than things which stand still or repeat in the same way. That was a good instinct in the time mankind lived in the woods, but it’s also very necessary to cross a street nowadays. Not all the incoming information gets through to our consciousness. Actually only a small part of it gets to our shortterm memory to be further analised, most of it gets thrown out.

Our brain is not blank when we are born, everybody is already different. But during the time we grow up our brain adapts to our lives, it makes more space where more space is needed. That means really that our brains are functioning very differently because we have had very different experiences. The virtual reality in our brain is always a mixture of incoming information and all the already stored information. That’s why we can never have the same interpretation of reality. If you and I go to a concert we don’t hear the same thing. If we put a microphone somewhere it will give us a third interpretation. Reality is there, but we can’t capture more than an individual interpretation. If we speak about a wineglas our interpretation may be pretty close. But if we talk about the beauty of a bow, we might be quite far apart.

Our brain works with expectations. With music, a certain combination of chords lets you automatically and unconciously expect a certain solution. Mozart’s genius was to build up an expectation and then give it us generously, but also give it a little unexpected turn, just enough to keep our attention. With bows there is a good chance that we will consider a bow to be beautiful, if the picture fulfills our expectations and at the same time gives it a share of unexpected details.If workmanship is too perfect we find it boring and cold. That’s because our brain continously corrects reality or fills it in, considering all the similar pictures that are stored in our memory.

We see the first letter from a word and we know it has to be the word “letter “ before we have read it. In fact we don’t even read it if it makes sense in the context, we just presume it is the word “letter”. When we look at a bow, from the very first moment our expectations will influence what we see. The picture in our brain (of a bow ) adapts only slowly to the actual bow that’s lying in front of us. In the virtual reality of our brain we even improve the design, at least if we understand the intention of the maker. When looking at an old bow we mentally heal the wounds of usage and doing so we start to build up a personal relationship with the bow, which I call sympathy. And that’s the main step to consider a bow beautiful. But how much we can relate to depends still on our personal experiences.

I hope it is evident that you can’t judge a bow objectively, but still you can try to describe it. A description is also some sort of a judgement, but perhaps we are more conscious of the subjectiveness of our evaluation.

10 Aspects on which to judge a bow

This list should make evident that there is more to it then just “good’ and “no good” , important is that a bow fits you and gives you the possibilities to express yourself as freely as possible. In the end it is you who makes the music.Soundstrong core, alot of high overtones, a strong middlerange,Volumeloud, low, focused, not so focused, good carrying power, no carrying powerWeightheavy, lightBalancegood, heavy at the tip, heavy at the frogString contacteven over the hole bow, not good at the tip, in the middle, at the frogBouncegood over the hole bow, regular, good only in one point, unregularStabilityis stable along the whole stick, breaks out to the side in the middle, at the frogStifnessgood, stiff at the frog, middle, tip, weak at the frog , middle, tipAestheticsnice tip, frog, beautiful wood, mother of pearl, gold , silver, nickel mountedFeelis comfortable in your hands, not comfortable

This list should make evident that there is more to it then just “good’ and “no good”, important is that a bow fits you and gives you the possibilities to express yourself as freely as possible. In the end it is you who makes the music.

12.0 Strip your bow

Chapter 12

I have been making bows for twenty-five years and I am still learning. At the moment my focus of interest is on the silver winding.

I was encouraged to go down this route of research through my friendship with Gordan Nikolic. He is an extraordinary violinist and a very inspiring person to all who come in contact with him. My deep admiration for his playing, and his infectious energy led me to explore new ground. We have spent many hours together trying out all sorts of different bows. The roles are very clear: he is the player and I am the listener. Sometimes I rehair his bow while he is playing, sometimes I sit in my armchair and just listen. Of course I always ask him to try out my new violin bows. Gordan and his playing are so familiar to me now, that I really feel able to hear and judge the bow for what it is. We are comfortable together and have developed trust and confidence over the years.

Recently Gordan came into the workshop excited by a new idea he’d got from a friend that all Tourte bows have their balance point at exactly 19 cm from the frog. He even wondered if 19cm was perfect for all violin bows. That was his premise and even though I was very skeptical, he pushed me to explore the idea further.